Art superheroes

Art is an amazing thing. It can inspire, inflame, create introspection or laughter, hint at horrors or joys, scream in your face or calm you with a story - it is and should be the conscience of our world. It has a memory that reminds us who and what we are - where we, in our humanity, went wrong or right at any given point in time. This aspect of art is especially important for those people who have been marginalized within our society. People of different genders, races, sexual preferences and/or cultures - those people who have been treated by traditional Western, male art discourse as “the other.” These are the people who deserve and need a voice, and through art, consistently have to work to make that voice heard.

As a female artist, it is important to acknowledge my own history. Those creatives that have stopped me in my tracks, and upon discovering their work, changed my life forever. Those who have helped me find a voice and a strength I never knew I had. This week, I do a shout out to four female artists that have impacted me along with the who, the what and the why.

-----

© Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your body is a battleground), 1989. Photo by Jeremy Thompson (Licensed under CC BY 2.0).

For those who know me, it is probably no surprise that Barbara Kruger has been a huge influence on my creative life. Her history in design, her signature Futura Bold Oblique text, her use of appropriated images - it is a mishmash of everything I love about photography, art and collage. Add to this an in-your-face style of critical discourse and kickass approach to unearthing stereotypes and there is little doubt that Barbara Kruger is one of my fine art heroes.

Kruger built her design chops working for Condé Nast Magazine and on publications like Mademoiselle and Aperture. During this time, her personal artwork included wall hangings made from craft pieces (such as feathers, yarn and beads). As Kruger discovered that her own path was not aligned with a career in the magazine industry, she left her work as a designer, and in 1979, exhibited her first artworks that demonstrated her trademark style - appropriated, enlarged photographs with bold blocks of red, white and black text.

Kruger’s work incorporates visual content from mainstream media - advertisements that are intended to push forward stereotypes around beauty, femininity and gender - and through this appropriation, she is able to redefine the intended message. By manipulating the presentation of the original photos (for example, by converting color scenes to black and white, using silk screen techniques or blowing up magazine size images to larger than life murals), Kruger has taken the expectations around what a woman should be and turned this into a question - not only about the original message but why these dictates are so easily accepted.

By adding in text blocks and using a confrontational, matter-of-fact communication style, Kruger critiques standards of femininity - the stereotypes that should have us all questioning why media and advertising continue to hold such a prevalent role within our society. On a personal level, Kruger’s work not only helped to inspire me to create but to realize, through art, that we as women, could and should fight back.

-----

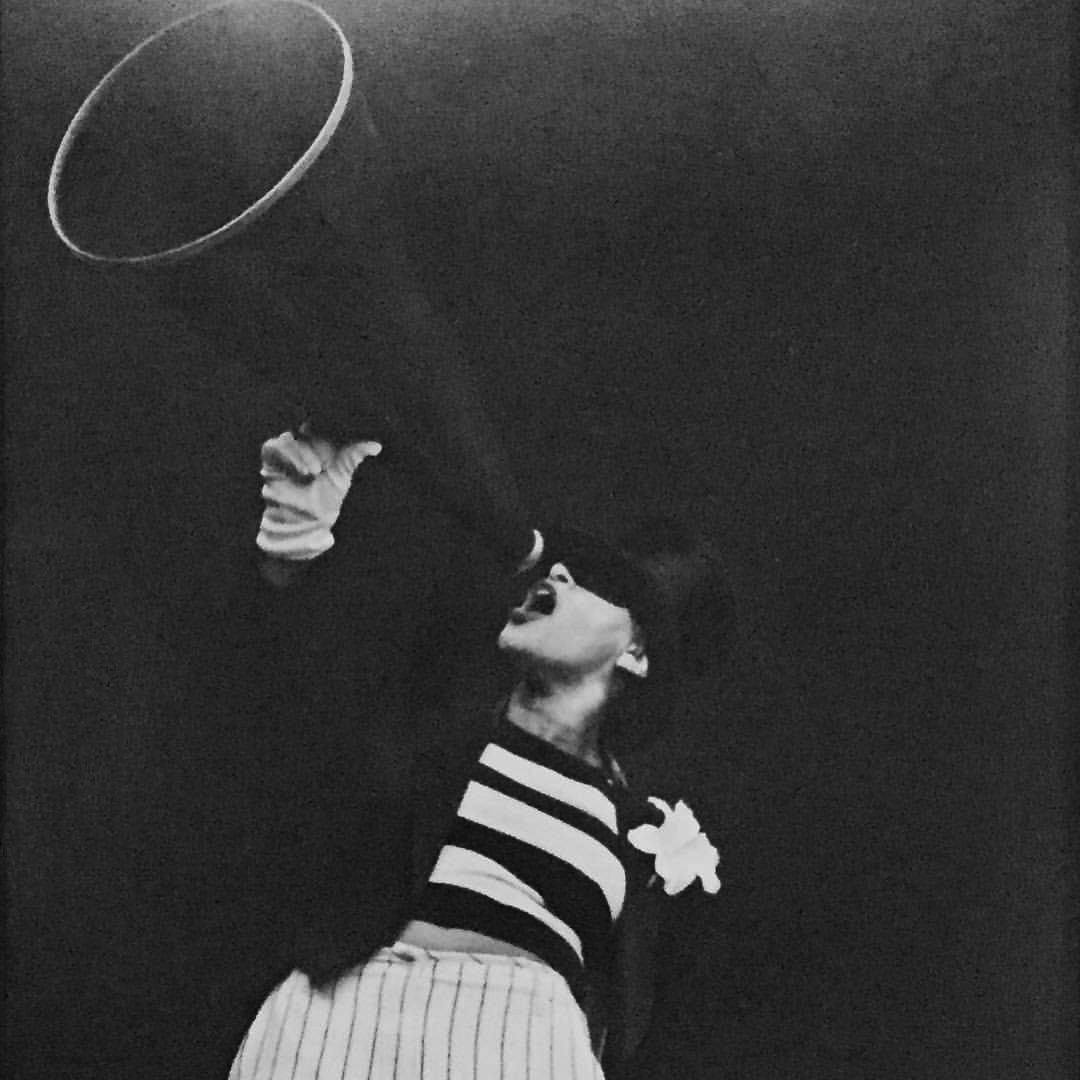

© Carrie Mae Weems, From Performance Gestures, 2004−07. Photo by Heidi De Vries (Licensed under CC BY 2.0).

Carrie Mae Weems is an artist who transcends the typical constraints that can be seen in an artist’s choice of materials. She has made works in text, fabric, audio, video and sculpture, but is best known for her photographic depictions. In her twenties, Weems was active in labor movements; later, she studied dance with artists like John Cage; and more recently, received a genius grant from the MacArthur Foundation. Weems is diverse and passionate about her interests, visible not only within these pursuits, but throughout her portfolio of visual work.

Weems has consistently explored issues of race, gender and politics. She gives the hidden nooks-and-crannies of our past a voice, and by doing so, impacts the contemporary discourse. In each series, Weems is able to explore these sensitive and controversial topics with honesty, beauty and strength - making the conversation accessible to a wide, expansive audience (regardless of background or personal history). The human experience - whether past, present or future - and its impact on our racial politics is a critical component in most works. For example, in the Kitchen Table Series, Weems uses her dining room as a backdrop - exploring stereotypes depicted upon those of African-American descent. In the Louisiana Project, photographed during the anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase, Weems explores the complex history of New Orleans as it relates to race and gender. By using plantations, railroads and other spaces within the New Orleans environment, she reminds the audience of stories that should never be forgotten and how they continue to relate to present day cultural constructs.

Especially impactful within the Louisiana Project are the “shadow scenes.” These stripped-down narratives, depicted in silhouette, bring to light the uncomfortable roles that exist within Western culture around the African-American experience. The history that we, as a society, try to sweep under the carpet, the racism and stereotypes that continue to be prevalent - these are exposed within the narrative. Weem’s voice - strong, proud, honest and direct - is one to be followed. It is a voice that art should embrace.

-----

© Eva Hesse, Untitled, 1968-70. Photo by Kimberly Potvin (All Rights Reserved).

Eva Hesse’s work is unlike anything else that came out of the 1960’s. Suffering under the strict structure and rigidity of the minimalist movement, Hesse’s goal was to challenge our own beliefs of what constituted order, beauty and logic - to confront head on the organized, formulaic art discourse of the time. Add to this the complexity of Hesse’s personal history - having fled Nazi Germany, her mother’s suicide, her own fight with cancer - these raw, uncontrollable moments of life can be seen in the visual evolution of her work.

Hesse’s sculptures are made up of materials like latex, rope and plastic. The ropes hang precariously from walls, organic-shaped vessels collapse in on themselves and latex-filled nets slowly fray and wear away at the seams. There is a balance - a precarious middle ground found between strength and fragility in each of these works. Hesse, through both the materials and the artistic process, shattered the standard definition of sculpture at the time. Not only was she working to deconstruct the strict confines of minimalist art but Hesse was developing the lexicon of post-minimalism while expanding its more organic form of expression.

On a personal note, Hesse’s work has always held my attention for other reasons. First, my feminist appreciation for latex as a medium. For many artists, especially within typical historical constructs (traditionally that of masculine painting), there is a strong desire for a legacy - the idea that an artist can last forever through one’s work. By embracing non-traditional materials like latex and rope, Hesse was able to break from this tradition and do so with the knowledge that her works would deteriorate over time - the wear and tear of the natural world would destroy that legacy. Second, for those who are unaware, Hesse passed away from cancer at the age of 34. This difficult fight and how it relates to my own familial loss has, in my mind, blended together with the overall message of her work. Whether intentional or not, Hesse communicates that life can be short, fragile, destructive and beautiful, and art, like the human body, may not need to last forever.

-----

Jenny Holzer

© Jenny Holzer, Inflammatory Essays, 1979-1982. Photo by Loz Pycock (Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0).

Jenny Holzer, like Barbara Kruger, is one of the conceptual female artists that came out of the 1980’s art scene. Holzer got her start by making large broadsheets with running blocks of text and wheat-pasting these fliers to structures around Manhattan. These truisms were statements - ones intended to instigate thoughts and reactions in an often unsuspecting audience. Participation could come in many forms - completing a half-expressed phrase; accepting a bold, blunt statement as fact or fiction; or, reacting positively or negatively to an assertive string of thoughts. The truisms were usually confrontational, and by incorporating a communication and presentation style often reserved for advertising, Holzer’s work had the power to sneak up on viewer’s consciousness - to utilize our cultural expectations around language to benefit the underlying message. By appropriating this guerilla-style tactic of art-making, Holzer was able to insert herself into the everyday thoughts of others - creating questions, impacting decisions and rerouting the daily thought patterns of her audience.

Like Carrie Mae Weems, Holzer is rarely restricted by her artistic materials. Although her best known works are large scale installations, projections on walls and LED lights, Holzer has made rubber stamps, glasses, plates, cards and paperweights. Her ability to select the best material for the message - especially those that are less commonplace within fine art circles - has been one that has helped to make her conceptual underpinnings more accessible to others. By usurping media often reserved for crafts or commonplace household objects, Holzer has opened up her work to a wider audience and removed herself from the rules and confines of the fine art gallery system.

Holzer’s truisms are confrontational. Whether questioning consumerism, confronting death or bringing to light the lack of clarity in our everyday political discourse, Holzer consistently uses text and language for maximum impact. Those who participate in her work can sometimes do so unknowingly, but through the message and the means, there is the opportunity to alter the direction of our cultural beliefs. With Holzer, this ability to push for change, to say what she means - loudly, strongly and visibly - has impacted not only my creative work but the way I communicate on a daily basis. By not speaking up and not speaking out, we as a society, condone questionable conversations and behaviors. We allow inappropriateness, stereotypes and inequality to continue. Holzer’s work has helped me realize, over time, that it is always worse to be silent than to be vocal.

---

For more information about these artists and others, jump on Artnet or Artsy and see what is out there. It is time to be inspired!